Editorial: Countering violent extremism, leading with harmony

Australia has been on a “High” National Terrorism Public Alert Level since September. But when Man Haron Monis took siege of the Lindt cafe in Sydney in December, the country was shocked. It’s appropriate to reflect on the lessons coming out of this tragedy, and also to take pride in our nation’s united response.

Man Haron Monis did not fit the classic violent extremist profile. He was not a trained terrorist. He was not a returned foreign fighter or radicalised, disaffected youth. But questions have been asked as to why this disturbed individual was not on the terrorist watch lists. And again, why this man charged with being an accessory to his wife’s gruesome murder, as well as 40 sex offences committed while posing as a ‘spiritual healer’, was on bail.

The attention-seeking ‘Sheikh Haron’ had just had his final appeal overturned in the High Court – his conviction for sending offensive letters to the families of deceased Australian soldiers and terrorist victims was upheld. This religious chameleon, a self-styled Shia cleric who was a recent convert to Sunni Islam, had the law descending upon him. He would make one last violent grab at the headlines.

ISIS has publicly issued blanket orders to its supporters in the West to commit solo terror attacks, by whatever means possible. Haron may have only recently claimed ISIS as his latest cause, and he may not have any actual connections to the terrorist organsisation, but he executed these orders to the letter. This ideology continues to hold a compelling attraction for some, and this case only proves that there is no predicting who might succumb to its appeal.

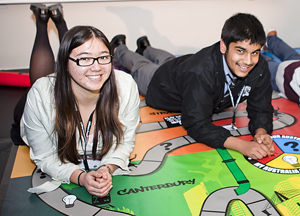

Perhaps the most endearing and enduring lesson has been the way the people of Sydney showed the world how Australians respond to terrorism.

If the real test for Australians is in how we respond to violent extremism, there are optimistic signs that we will not allow it to affect our way of life.

Within government, counter-terrorism attention had been focused on the 70-or-so Australian foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq and the many more sympathisers supporting the ISIS cause from Australia.

The threat remains real and present. Australia’s national security agencies succeeded in thwarting the Pendennis network, who conspired to carry out a large-scale terror attack in 2005, and whose numbers included individuals with foreign fighting experience in Afghanistan. One of the Pendennis network, Khaled Sharrouf, left for Iraq on his brother’s passport after serving his sentence. He then gained notoriety after posting photos of his seven-year-old son holding a decapitated head on social media.

In September, intercepts of ISIS communications ordering an imminent ‘demonstration killing’ of a random member of the Sydney public prompted Operation Appleby, the largest counter-terrorism operation in Australia’s history. The raids may have disrupted an attack, but with charges laid against only one person, the public was left with many unanswered questions and some Australian Muslims were feeling targeted.

Tensions were starting to run high. Muslim women had reported being verbally abused, and in some instances, physically attacked and having their headwear pulled off. Far right-wing extremists exploited a mood of fear, finding new fuel for their anti-Muslim rhetoric, with calls to boycott halal food products and protests against mosque development proposals.

In the aftermath of the Sydney siege, reactive extremism remains a risk: the Australian Defence League, a local offshoot of the English Defence League, has called for supporters to gather and protest in Sydney’s diverse south-western suburb of Lakemba, home to many Australian Muslims.

There are extremist minorities on both sides – pockets of ISIS-sympathisers, and small far right-wing networks espousing hatred of Islam – each feeding off the rhetoric of the other. The spill-over effects of this ideological conflict remain a real threat to community harmony and must be closely monitored. Some people will use this tragedy to propagate their own ideological agendas.

Police investigations under Operation Appleby are continuing. In fact, only hours before the siege started to unfold, two more individuals were arrested in Sydney, suspected of financing ISIS terrorism. On the Thursday evening following the siege, more homes were raided in suburban Sydney. These investigations may bring more threats to light.

Counter-terrorism laws, de-radicalisation programs, and social programs addressing ‘at risk’ youth all serve their purpose in countering violent extremism. The sad reality is that we may not predict or prevent another ISIS-inspired attack.

But Sydney has shown the world how best to respond to violent extremism in all its forms. The spontaneous expression of compassion and unity after the siege, typified by the Twitter hashtag #illridewithyou and the impromptu flower memorial attended by thousands, brings much hope to our common fight for peace. Sydneysiders have united in grief and transcended cultural and religious differences.

If the real test for Australians is in how we respond to violent extremism, there are optimistic signs that we will not allow it to affect our way of life.

Protecting each other from fear, hate and violence and standing united in hard times is how we can best ensure Australia’s national security, and our freedom.

The Point

As a community, we must counter violent extremism and work towards harmony

Author Note

Feature image courtesy Polair